Champernowne graphique

(et autres décimalisations)

J’ai envoyé par courrier privé à Jean-Marc Falcoz et Maximilian Hasler l’idée suivante :

> prendre la constante de Champernowne et embarquer pour une promenade en suivant, chiffre à chiffre, ces instructions :

- quand le chiffre est pair (0,2,4,6,8) on effectue un virage de 90° à droite puis on marche tout droit en effectuant respectivement 0, 2, 4, 6 ou 8 pas ;

- quand le chiffre est impair (1,3,5,7,9) on effectue un virage de 90° à gauche puis on marche tout droit en effectuant respectivement 1, 3, 5, 7 ou 9 pas.

Jean-Marc et Maximilian furent intéressés et se mirent à calculer.

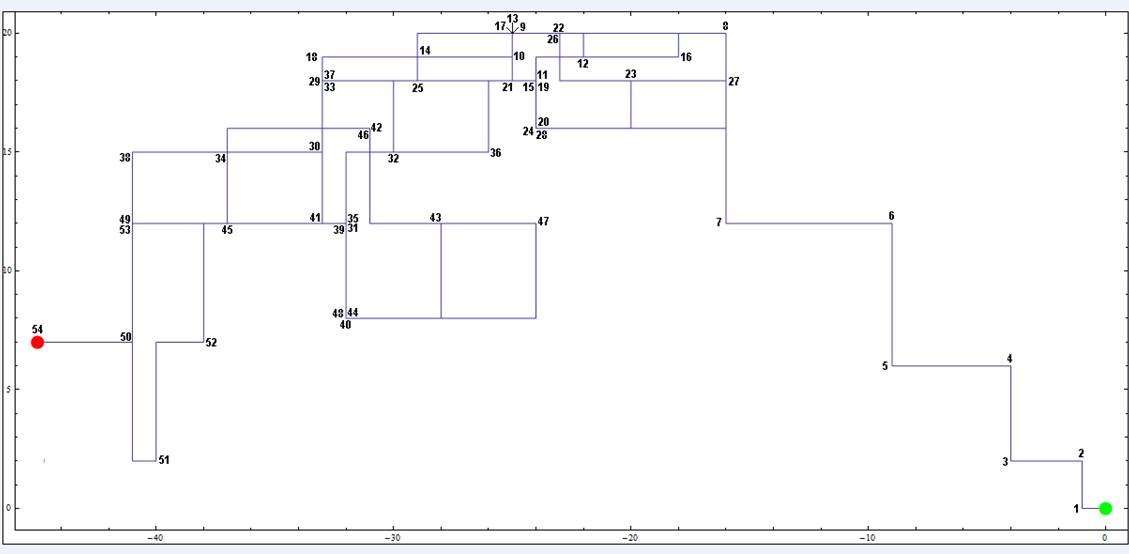

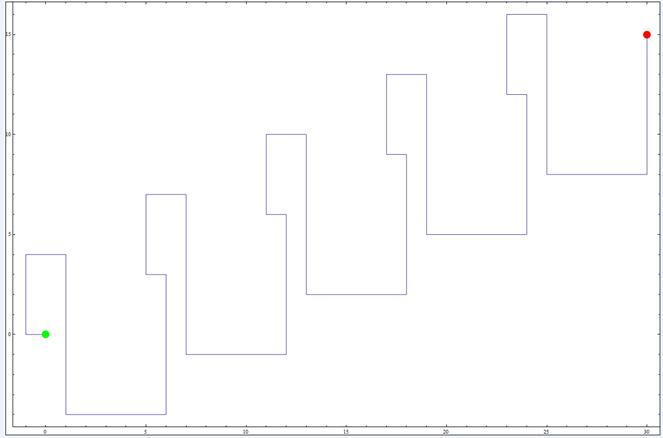

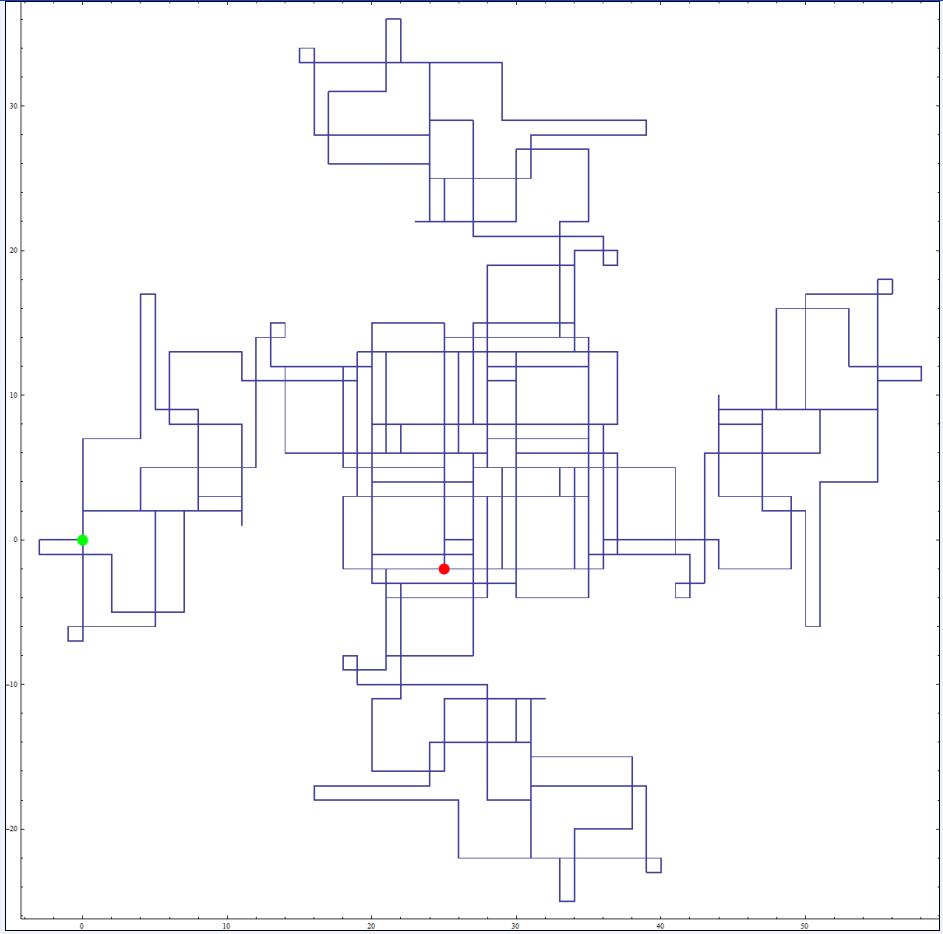

Voici, en guise d’exemple, comment aller de 0 à 54, chiffre par chiffre – départ en bas à droite, sur le point vert et arrivée près du bord gauche (illustration de Jean-Marc Falcoz) ; attention, le traitement du zéro est délicat (pour mon premier essai de dessin, je me suis fait reprendre comme un bleu par Jean-Marc et Maximilian) :

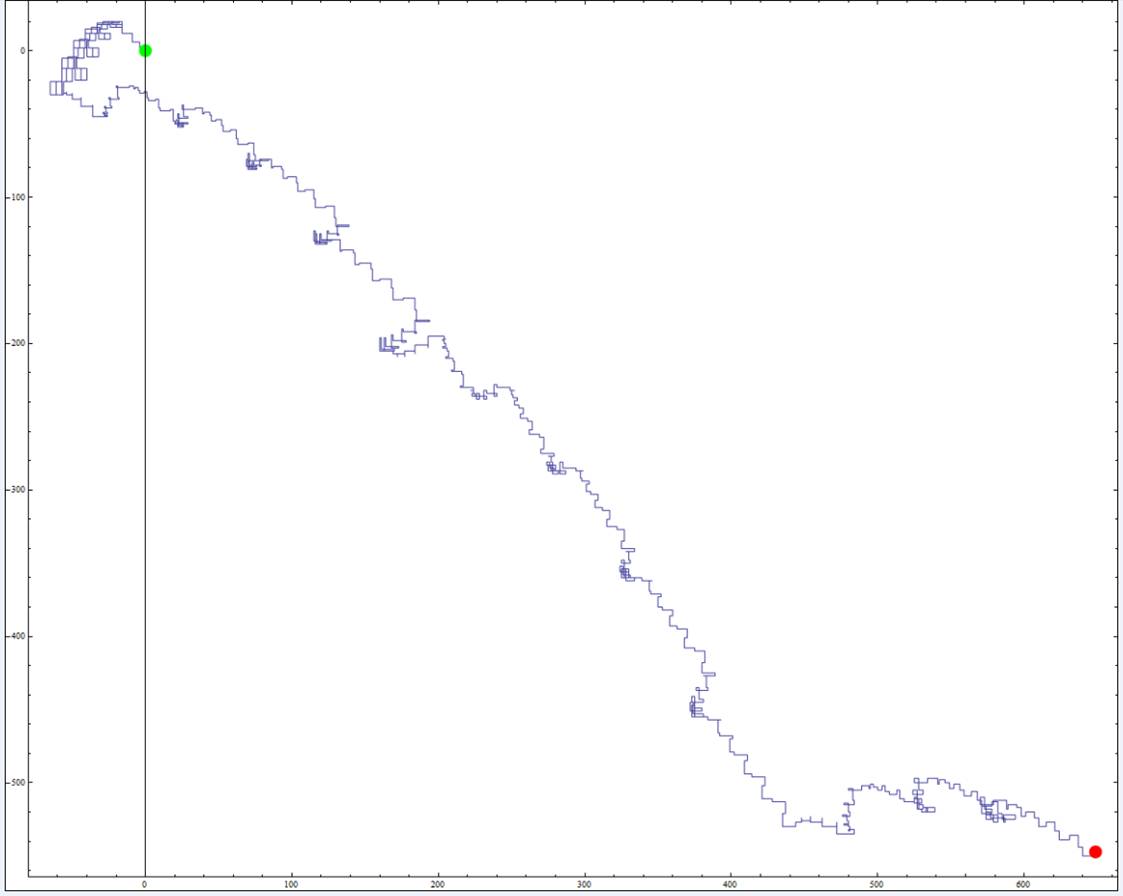

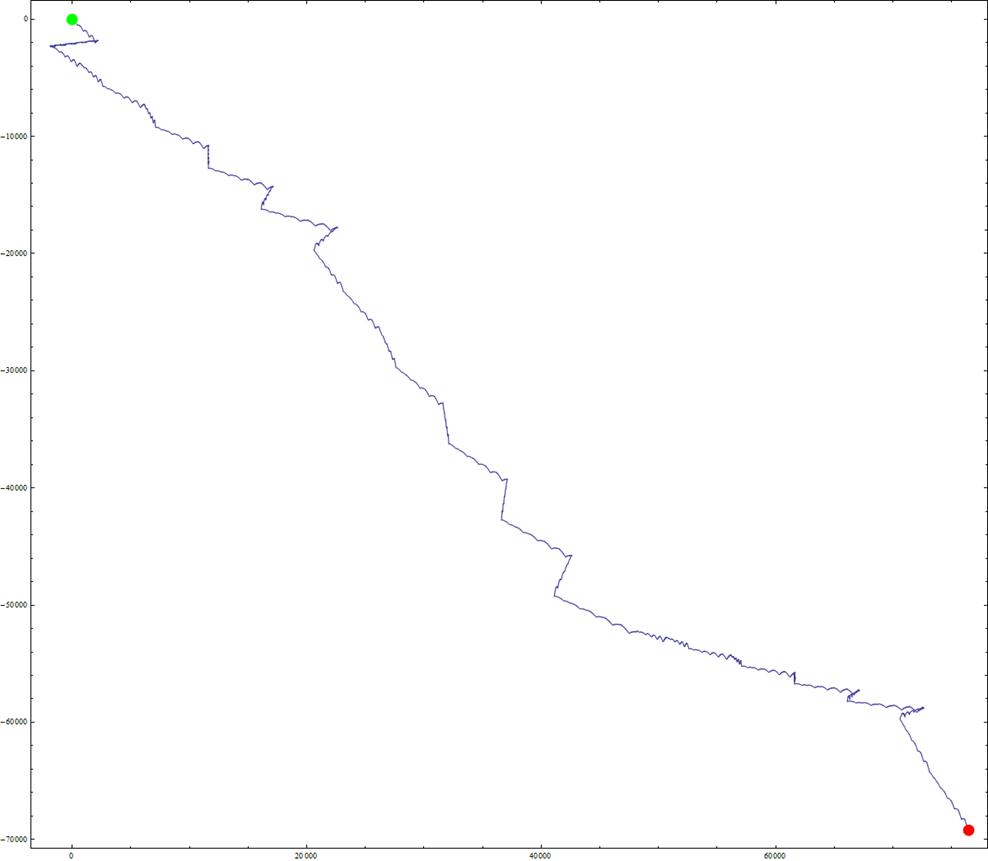

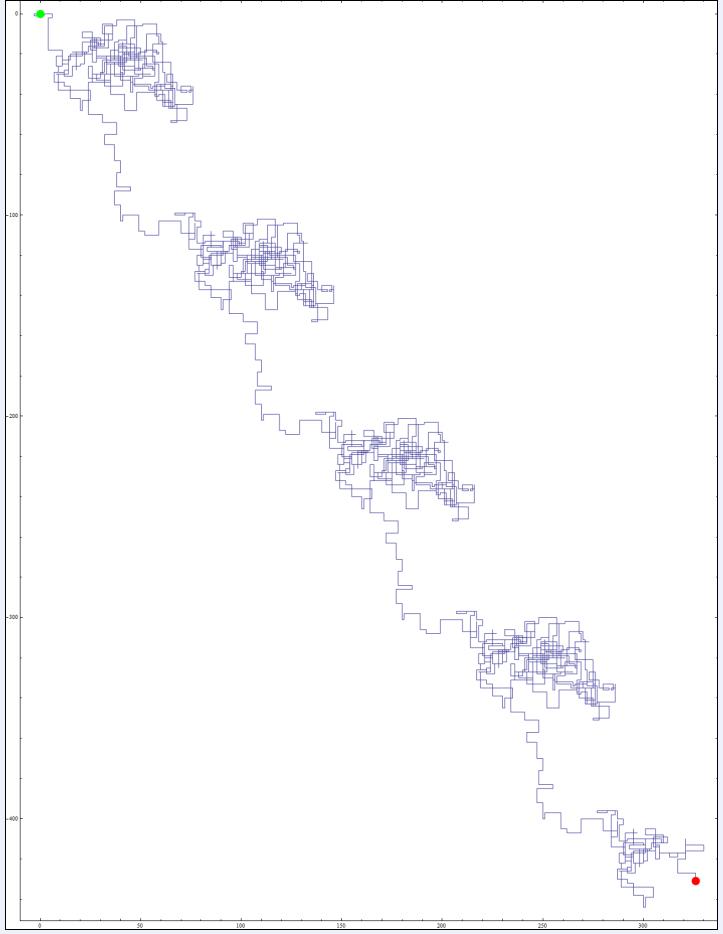

... Voici les 1000 premiers chiffres du nombre de Champernowne, dessinés par Jean-Marc Falcoz (le trajet commence au point vert (0,0) en haut à gauche, monte un tout petit peu, descend, change de cadran une première fois, puis une seconde fois – et finit par s’enfoncer inexorablement le sud-est) :

Calcul par Jean-Marc des 1000 premiers entiers concaténés :

Confirmation de cette trajectoire – calculée indépendamment par Maximilian Hasler :

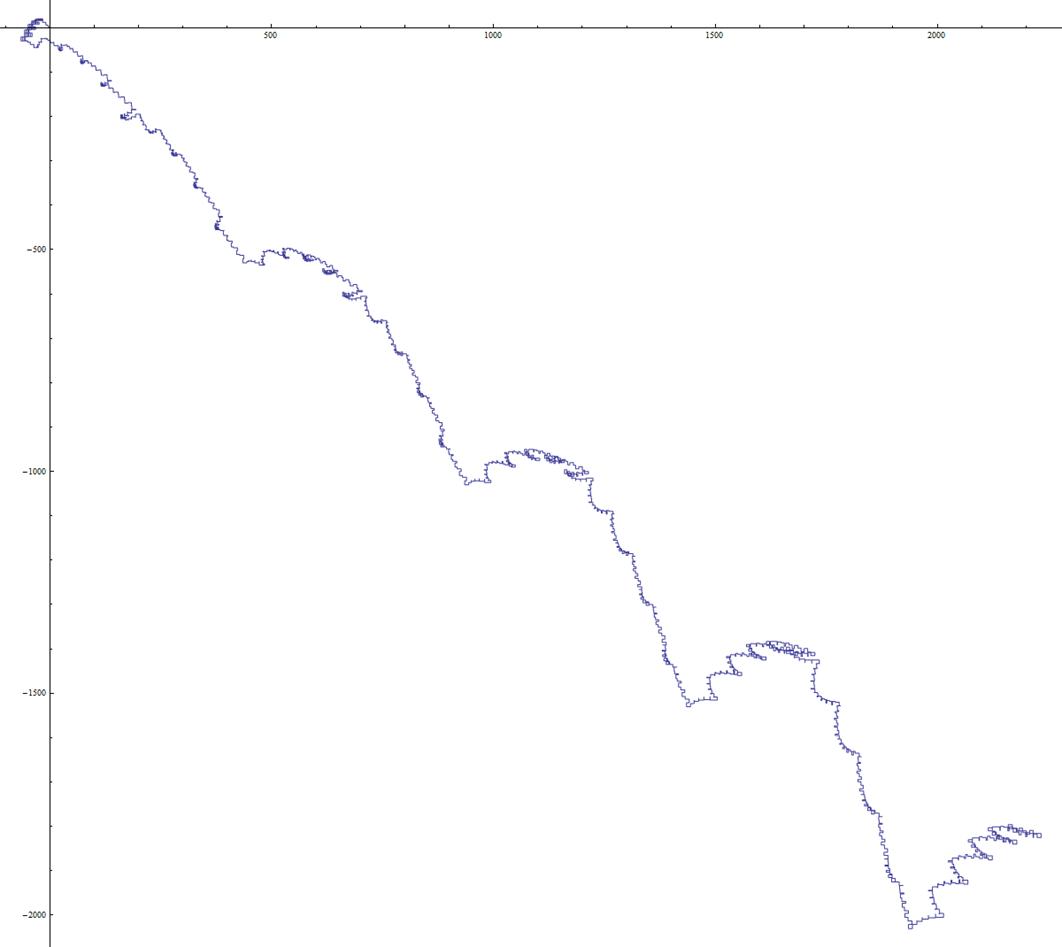

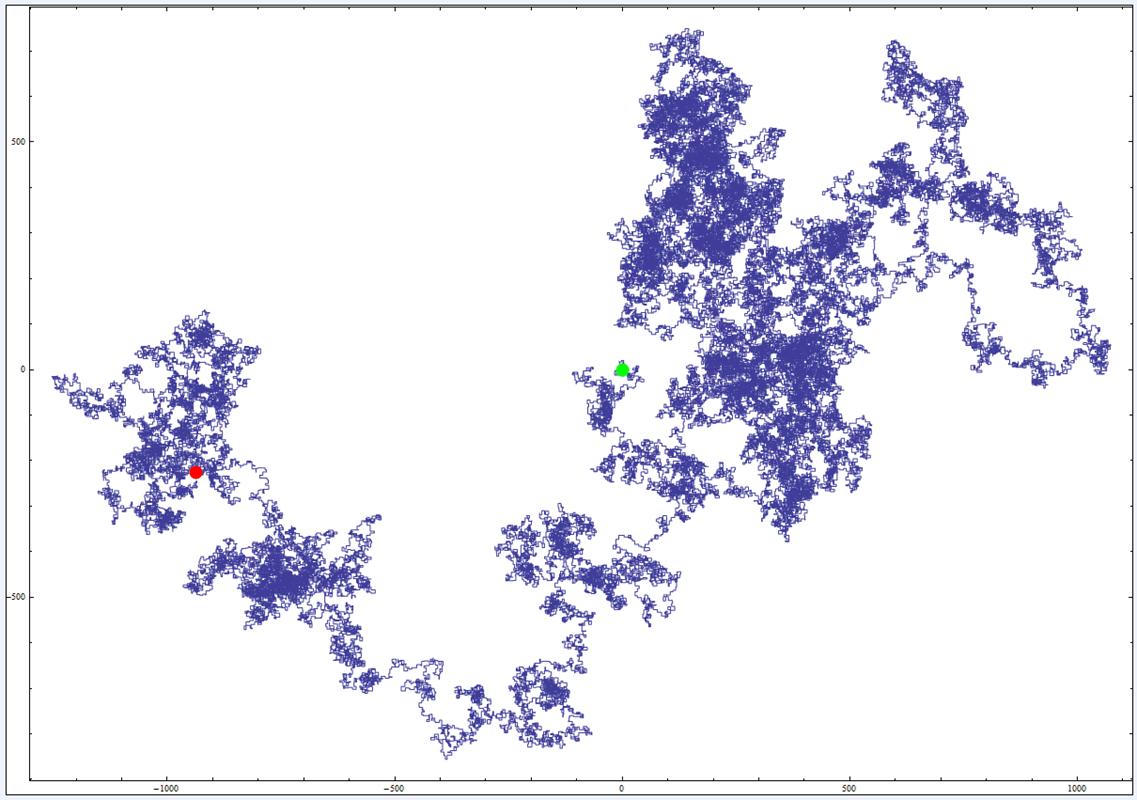

... Ci-dessous, les 10000 premiers chiffres du nombre de Champernowne, dessinés par Jean-Marc :

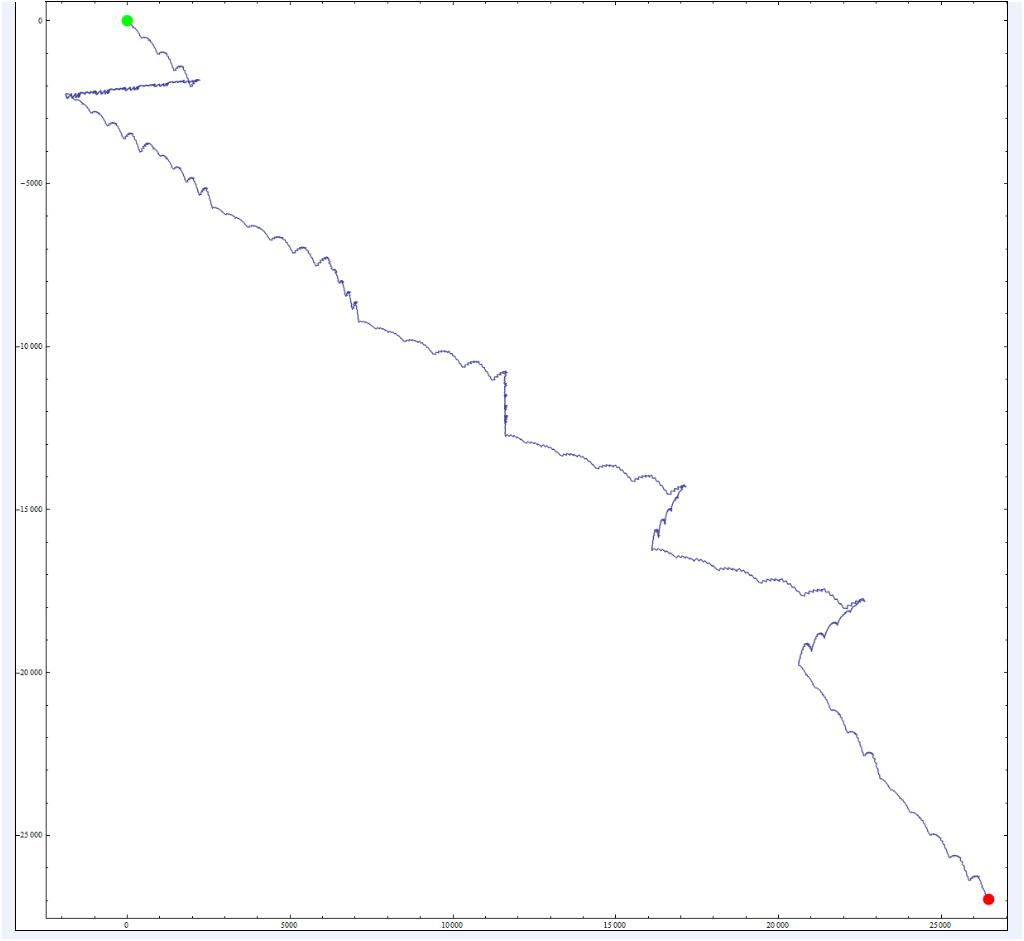

... et les 200000 premiers chiffres du même nombre de Champernowne, toujours par Jean-Marc :

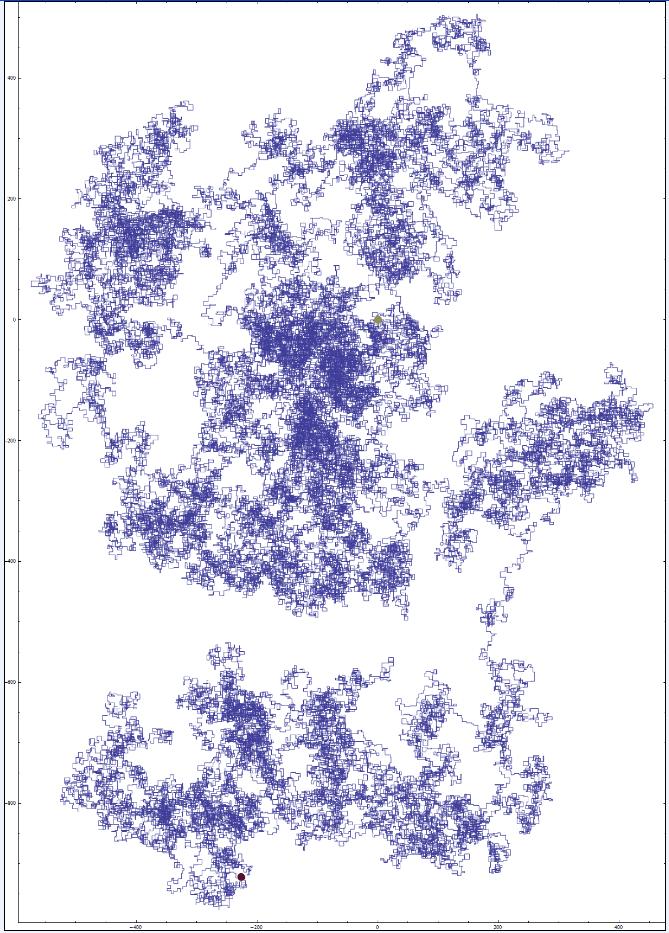

Voici les 100000 premières décimales du nombre « e », allant du point vert au rouge (toujours par Jean-Marc) :

10000 décimales de Pi (du point vert au point sombre, en bas), par Jean-Marc :

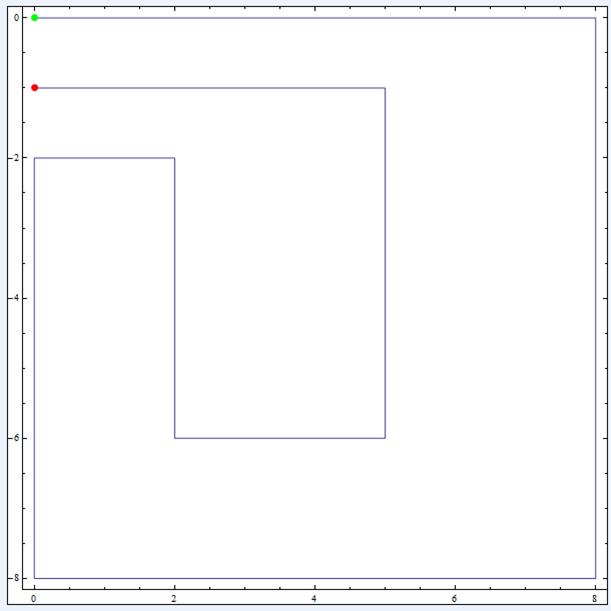

Jean-Marc a eu l’idée de représenter des nombres ayant des décimales qui reviennent périodiquement ;

1/7, par exemple, produit à l’infini le motif « en escalier » suivant :

La fraction 1/317 boucle sur elle-même :

La fraction 1/317317 cascade infiniment vers le sud-est :

Jean-Marc a plein d’idées encore : qui calculera, par exemple, la suite des entiers tels que 888624355 ? Ils n’ont aucun point par lequel leur trajectoire ne repasse :

More to come, stay tuned!

__________

A last word (for

today) by Jean-Marc:

Je viens de faire un

programme qui trouve et affiche graphiquement les nombres dont les trajectoires

commencent et finissent en (0,0), ne se croisent pas et ne repassent pas deux

fois par le même point (on fait une exception pour les 0 internes (la

trajectoire d’un nombre contenant par exemple ...807... on pourrait considérer

que la trajectoire passe deux fois par le même point à cause du 0, mais comme

le segment en question a une longueur nulle, je ne considère pas qu’elle

repasse deux fois par ce point) :

__________

[Breaking news]:

Voici le message posté ce matin par Maximilian à la liste SeqFans:

Dear

SeqFans,

inspired by a private communication

from Eric Angelini,

I

suggest a new(?) [integer]

sequence transformations

(plus some variants), which I tentatively call "Turtle

transformation"(s)

(in memoriam of the turtle graphics in the Logo programming

language)

The

complex Turtle transformation of a sequence

a : n -> a(n) , n >= offset ;

is the sequence obtained from a(n) by

1) defining a sequence of "directions"

d(n) = d(n-1) * i * (-1)^a(n) ;

d(offset-1)=1

2) then the Turtle transform is the sequence of partial sums of

"steps

of length" a(n) "in

direction" d(n), i.e., d(n)*a(n),

T(a) = n -> sum_{k=offset...n}

d(k)*a(k) ; T(a)(offset-1) = 0.

The

interpretation is that T(a) represents a

"walk" in the complex plane,

where at the n-th

step, the "cursor" turns to the left or to the right

depending on the parity of a(n), and

then walks a distance of a(n)

units.

This

in turn gives rise to at least 3 (integer) sequences (if a(n)

is

an integer sequence), namely

Re T(a) ; Im T(a) ; and

S(a) = these two interleaved, i.e.

S(a)(2n-1)=Re

T(a)(n) ; S(a)(2n)=Im T(a)(n).

There

are several variants possible:

a) use abs( a(n) ) instead of a(n) in case of a signed sequence

(this will destroy bijectivity)

b) don’t use only left or right turns depending on parity, but

rather

a

turn of 90° * a(n).

c) use a second sequence, b(n), for the "turns", to

define the

b-Turtle

transform of a(), say T[b](a) or T(a ; b) = sum( d[b](k) *

a(k), k=offset..n

)

with

d[b](n) = product( i^b(k) ; k=offset...n

) [or prod( i * (-1)^b(k)...) ]

d) use some other initial condition for the direction (a priori

just

amounts to a multiplication by a unimodular number of the transformed

sequence)

or, e.g., the opposite convention for

turning left or right (which

should correspond to a change of sign and/or

complex conjugation).

It

is easy to see that both, the b-Turtle and (a-)Turtle

transformation, are bijective.

For

sequences with only odd numbers, such as the primes, the variant

(b) above is more "interesting". I will denote it by

T’, and look at

its action on prime=A40:

It

turns out that T’(prime)(56) = -13+8*i, i.e., almost

exactly back

to the origin, after having made an

"excursion" as far as 702 - 1197*i

around n=46 ;

then again the cursor goes away to

T’(prime)(78) = -2922 - 1733*i,

before "crossing" the origin during

the 99-th step,

going from -256 + 37*i to 267 + 37*i.

Just

for the fun, I submitted that sequence as oeis.org/draft/A233399

,

including the picture after step 99 (drawn in red),

https://oeis.org/A233399/a233399_1.png

Maximilian

__________

La réponse à Maximilian

par William Keith :

>

I did something like this for primes, although the rule was simply to make

a left turn at node n of the walk if n

was a prime. The results, turned to

graphics using Mathematica,

can be found at

http://earl.of.sandwich.net/Photos/Images/PrimeWalks/

With

sufficient magnification you can see where the 1 is, since it's the

only short end. For example, in

PrimeWalk3080(1899x1173).jpg it is on the

left.

William

Keith

(...or, upon second glance, I think I turned right.)

__________

Illustrations (c) Jean-Marc Falcoz & Maximilian Hasler

[9 décembre 2013]